The very first .357 Magnum is still first in the hearts and minds of many advocates of that caliber. This milestone revolver continues to morph into the future. See why, when you read this article from Massad Ayoob.

The very first .357 Magnum is still first in the hearts and minds of many advocates of that caliber. This milestone revolver continues to morph into the future. See why, when you read this article from Massad Ayoob.Read more »

A George Finegold Blog

The very first .357 Magnum is still first in the hearts and minds of many advocates of that caliber. This milestone revolver continues to morph into the future. See why, when you read this article from Massad Ayoob.

The very first .357 Magnum is still first in the hearts and minds of many advocates of that caliber. This milestone revolver continues to morph into the future. See why, when you read this article from Massad Ayoob.

Conventional wisdom says a 12-gauge shotgun is best for home defense. I disagree with this conventional wisdom. To my way of thinking, the best gun for home defense is (drumroll please) ... the gun you can get to in a hurry and use efficiently.

Whether or not that's a shotgun, a rifle, or a handgun depends entirely upon you and your circumstances. But there are some strong reasons to consider the handgun as a good tool for a home defense gun.

A handgun is easily transported around the house, invisible to friends and casual callers but still within your direct control at all times. It is easy to answer the doorbell armed with a handgun, without anyone being the wiser. The handgun can even be drawn, discreetly concealed behind one leg as you open the door. Unlike a long gun, a handgun can always be available for instant use without unnecessarily threatening legitimate callers.

Handguns are also most easily kept accessible to adults but out of the hands of small children, more so than shotguns and rifles. As I've written elsewhere, when our children were very small, I soon began to develop a well-earned skepticism about my ability to know what the little darlings were up to in the next room. The kids, bless their active little hearts, gave me more than a few exciting little lessons about why I should not trust "child-proof" locks, or (worse) simply rely on their good natures to stay out of trouble. And the day I found a two-year-old sitting on top of my refrigerator, I realized that putting things "up high where the kids can't get it" was just a sick little joke.

With children in the home, the gun that is out of adult sight absolutely has to be locked up. But it is really a lot slower and less certain to get at the gun in a hurry if you have to force your terrified brain to remember a combination, or persuade your trembling fingers not to drop the keys or fumble them. When faced with an immediate and deadly danger, even split seconds count.

Keeping the home defense gun out of my children's hands was problem one. Problem two, of course, was being sure I myself could get to the gun quickly enough if the unthinkable happened. I kept thinking about this second problem, and the more I thought about it, the less happy I was.

Experts generally agree that the best plan for a home defense situation is to get yourself and your family behind a single locked door, such as in the master bedroom or some other "safe room." Then you can hunker down behind some large piece of furniture and await events with gun in hand. If the police arrive first, they can deal with the intruder for you. If they don't, you can protect yourself until they do arrive.

So it did seem to me that the sensible place to store my home defense shotgun, if I got one, was behind a good lock somewhere in my bedroom. Maybe it would be out of sight too, but definitely locked up where the kids could not get it. The inherent slowness of a lock worried me, but once I got the gun unlocked, it would be available if I awakened to the sound of a home intruder.

But what if I wasn't in my bedroom when an intruder entered? What if I was, instead, in the front room with the children? Would I leave my children in the same room as the intruder in order to go fetch the long gun from my bedroom? What if, as soon as I bolted for the firearm, the intruder picked up one of my children and simply ... left? Perish the thought!

I found myself thinking, There has to be a better way.

There was. Rather than struggling for ways to store and then to quickly release a long gun locked up in some out-of-the-way location at the back of the house, I could instead keep an easily accessible handgun in a holster on my body when I was at home. That solved both problems.

First, while I might not know what my active little sweethearts were up to in the back room when the house went suspiciously quiet, I would always know whether or not their little fingers were prying the gun out of the holster on my hip. In this way, the loaded and easily accessible handgun on my hip was actually more secure than the "securely locked" long gun in another room.

Second, with the gun on my belt (or in a fanny pack) at all times, there could be no question of having to abandon the children to the tender mercies of an intruder while I ran to fetch a gun. The gun would be with me and instantly available.

| Sleeping |  |

At this point, some of my readers are probably wondering how in the world I keep a handgun on my body when I sleep. I don't, of course.

At night, I habitually lock my bedroom door. I have done this ever since my children were very small. We used to have a row of baby monitors, one for each of the kids' rooms and for the living room, lined up on my dresser at night. If one of the kids awakened in the night, I would know it -- and I would know it before the adorable munchkin dropped a full cup of juice on my face as I slept, or vomited onto my pillow just as I opened my eyes. 1

Behind my locked bedroom door, the gun is secured in a fanny pack placed inside an open safe. Inside the fanny pack, there's a flashlight, a charging cell phone, and a spare magazine with extra ammunition -- any of which I might need in a hurry if an intruder is in our home.

If something awakens me in the night, I can quickly pull the fanny pack on over my robe. Looks goofy, but it works. If I don't want to take the gun with me, I simply swing the safe door shut and lock it before unlocking my bedroom door.

| Tactical Stuff |  |

During an emergency, a handgun can be carried in one hand, and can instantly be deployed with one hand. This emphasis on one-handed use might sound a bit silly to someone who does not expect to get injured during a crisis. Why would you need a gun which can easily be fired with one hand?

An injury to one hand or the other really is not outside the realm of possibility. But even if we set that aside and do not consider it in our planning, you may very well need one hand free to do things like open or close bedroom doors, tote the phone, keep a tight hold on a child's hand, or carry a baby across the hall to the safe room. Any or all of these things may need to be done during a home invasion, and few of them can be done well (or at all) while carrying a long gun.

Whether you decide to use a long gun or a handgun for home defense, it is really a good idea to get some practice in close-quarters work. That means learning how to defend the gun from a sudden and unexpected grab, and also how to get the gun away from an opponent who has already gotten his hands on it. Which is easier to defend against a grab, a long gun or a handgun? That all depends. My personal experience has been that it is easier to prevent a handgun from getting grabbed in the first place, but if there's room to work, a long gun provides a lot of wonderful leverage to help you defeat the grab. Neither defense is instinctively natural, and both have to be learned from someone who knows the secrets.

It is generally a bad idea to move through the home when intruders are present. As mentioned above, experts strongly recommend you just hunker down in a safe room with your family rather than wandering around looking for someone to kill you. But realistically, this hunkering-down is not always immediately possible. You might need to grab a young child and bodily move her to the safe room with you, for example.

If you do need to move through the home with gun in hand, handguns are generally easier to deal with while moving around corners and in tight spaces. Remember the intruder could be hiding anywhwere, and may be waiting for the opportunity to grab you or the gun. Even people who are highly trained sometimes have a hard time moving around corners with a long gun, without allowing the barrel of the long gun to precede them around the corner. This is less likely to happen with a handgun.

| Other Considerations |  |

Money was an issue too. I'll admit that right up front. An important budget item to consider for any defensive weapon is training. I trust my handgun because I have trained extensively with it. I know how to load it and unload it. I know how to shoot it accurately, how to clear jams, how to reload it, how to fire accurately while walking, running, moving, hiding behind cover. I learned all those things in classes where talented (and stubborn) instructors taught me the most efficient ways to do them. And I have practiced with the handgun so much that it feels very nearly like an extension of my hand when I am holding it.

Could I get all that training and do all that practice with a long gun? Of course I could! But I already had the handgun, and was already getting handgun training. Although from the size of this website, you might think I'm a little obsessive about firearms, the truth is that I have a whole lot of other things to do with my time and money. Learning a new firearm as well as I already knew my handgun, would have literally doubled the amount of time and money I spent on training. For me, given my budget and time constraints, it just made more sense to focus all my training time and training money into learning one system really really well.

If you are a concealed carry permit holder, you probably consider the handgun an acceptable defensive choice while you are out and about during the day. All other things being equal, it will be less expensive and simpler to just use that same defensive firearm at home at night, too. The handgun might produce less overall power than the shotgun or the rifle, but it is no less effective at home than it is when you are out and about. And you trust it with your life when you are out and about.

But if carrying a handgun at home seems too much of a hassle to you, and if you do not have small children to complicate the issue, or if you are able to secure a long gun in such a way that you are confident you could get to it in a hurry, then a shotgun or carbine may indeed be the best choice for your home defense.

| Reasons to Avoid a Long Gun |  |

Rifles and shotguns do have a lot going for them: power, ease of aim, and the intimidation factor. Shotguns offer another important benefit, which is the huge versatility of ammunition choices. But long guns are also bulky, do not lend themselves to being discreetly carried to the door when someone knocks after dark, and are not easily kept quickly accessible to responsible adults while safely secured from children and the clueless. They can't get dropped into a fanny pack and it's difficult (not impossible with adequate training) to operate a long gun one-handed. These drawbacks are worth taking into account too.

The myths about a shotgun not needing to be aimed, or about the mere sound of it driving intruders off, are just that: myths. Don't bet your life on those! But like all myths, both of these have a small germ of truth hidden inside them: a long gun is easier to aim than a handgun, and shotguns are powerful enough that a marginal hit may be enough to do the job anyway.

As for the sound being enough to drive an intruder away, if you have not squarely faced and accepted the notion of killing someone else to defend your own life, a firearm -- any firearm! -- is nothing but a dangerous nuisance. If that's a factor for you, you need to get your own ethical/moral/religious issues worked out before you arm yourself with a deadly weapon.

| Conclusion |  |

The best gun for self-defense is the one you can get to in a hurry and use efficiently. For me, that was a handgun. For you, it might be something else.

Whatever you choose, take careful thought to how you will safely secure the firearm. Purchase appropriate accessories for it. And get training in how to use it effectively.

(Photo Tim Dees)

Rotating

When the magazine springs for your firearms give up the ghost, don't throw that magazine away. Brownells sells replacement magazine springs and keeps your costs down for maintaining your firearm. There are many other reputable gun accessory vendors that can supply these and other items to keep you ready for the street.

Semi-automatics: Remove the magazine. Then lock the slide open and visually look in the chamber. Poke a finger into the magazine well to be sure it is empty. Then run the tip of your pinky finger into the chamber to be sure that there's a hole in there rather than a live round. Look again before you close the slide.

Revolvers: Roll the cylinder open and visually count the chamber holes. Then run your finger over the holes and count them again by feel. Visually count the holes again before you close the cylinder.

To a newcomer, using your fingertips as well as your eyeballs to be certain the gun is unloaded may sound a bit obsessive. But it's really not obsessive. It is simply a good safety habit.

In the pictures below, I've unloaded a revolver for you to look at. You should just glance at this first picture. The gun is unloaded, right?

Use the tip of your finger to |

For the record, the photos don't cheat. The gun in the second photo is in the exact same condition as it was in the first photo -- loaded! The only difference is that the cylinder was not rolled out all the way in the first photo, which is a really easy mistake to make if you're just glancing at it for a quick check when you already "know" it's unloaded.

This is why we check twice with our eyes, and touch the holes. When distracted or under stress, it is surprisingly easy to miss seeing things we really didn't expect to see anyway. And it is just as easy -- or easier -- to do the same with a semi-auto, and miss seeing the round in the chamber or the magazine in the butt of the gun.

So use your hands as well as your eyeballs to check, and never take anything for granted.

Here is how to determine y our dominant eye:

- Take an 8 x 11 inch sheet of paper and in the center of the paper, use a pencil to punch a hole in the paper.

- Hold the paper with both hands at arms length.

- Keeping both eyes open, look through the small hole as you slowly bring the paper back to your face.

- When the paper touches your face, the hole will be centered over your dominant eye.

If your dominant eye is the same as your dominant hand, then good for you. You are normal and unremarkable! (That’s a joke.) You are like 90% of the other gun owners in this country.However, if your dominant eye is opposite of your dominant hand, then you are Cross Dominant and will need to make some decisions before embarking on serious training.No need to worry. You can still train to the highest levels in the world. I know. I’m a Four Weapons Combat Master and I am cross dominant. I am left handed and have a dominant right eye.So here is what you do:

With a long gun: Shoot with your dominant hand keeping both eyes open until that fraction of a second when you need to shift the focus on your eye to the front sight, then simply close your dominant eye. Your non-dominant eye is now the dominant image forcing your brain to use the non-dominant eye to focus on the front sight.With a handgun: You can use the same technique or simply tip your head a bit and focus on the front sight with your dominant eye.Those two techniques above=2 0are the easiest fix for Cross Dominance.

The holy grail of practical shooting is when you get to shoot OPA, or "other people's ammo". Now you have a chance to do just that, except without having to practice or wear a silly colored shirt. HPR Ammo is a new ammo manufacturing company out of Arizona that is spooling up for production.

They're having a raffle to give away ammo to 100 lucky customers that will get their pick of .223, .40 SW, 9mm, or .45 ACP! Nothing beats shooting other people's ammo, so get to their website at HPR Ammo to sign up.

Posted by Marty Gartenberg

Police, military, and concerned citizens must objectively and thoroughly choose a handgun which fits their needs. The decision is quite difficult as the list of handguns is long and there is no perfect handgun, no perfect caliber, and no perfect bullet. Available accessories may also affect the decision; read on to find some pointers that may help you think of aspects which you may have overlooked.

This is a contentious topic on firearms boards. Every gun owner seems to have an opinion about it, and some get quite irate if you don't agree with theirs.

The truth is that every gun is a compromise. Neither revolvers nor semi-automatics are perfect in all respects. Which one is right for you depends upon what your priorities are, and upon what you are willing to give up in order to achieve those priorities.

The list below is alphabetized. It isn't in order of what I think is most important, because what's most important to me may not be as important to you.

A revolver will often allow the user to load two different calibers of ammunition (.38 Special and .357 Magnum, for example), allowing greater flexibility for the user.

A lightweight revolver can often carry more powerful ammunition than a semi-automatic of equal weight.

At the low end of the scale, really cheap revolvers are usually more reliable than really cheap semi-automatics. Again, this is because revolvers are simpler machines.

When buying a used gun, it is somewhat easier to check out a used revolver than it is to inspect a semi-automatic, and revolvers are somewhat less likely to suffer non-obvious problems that affect function.1

However, once you've learned to do that, even with the disassembly/reassembly process, it's usually faster and easier to clean a semi-auto than it is to clean a revolver.

However, it isn't that hard to learn the basic operation of a semi-auto. A semi-automatic handgun is less complicated than a washing machine or a car, and every normal adult in America is able to understand both of those complex machines at least well enough to run them.2

But it isn't always quite that simple and clear-cut, in my opinion and experience. I've met women who couldn't manage a double-action revolver trigger at all, but who had little trouble racking the slide of a semi-automatic when shown the correct technique (see article titled Rack the Slide for more information). It all depends upon which part of your hands are weak, and what the causes are for your weakness.

As a side note, if your hands are so weak that it is difficult for you to pull the trigger of a double-action revolver, and you also have difficulty racking the slide of a semi-automatic, you may want to look at Beretta's tilt-up barrel semi-automatics. These are semi-automatics which do not require the user to rack the slide for loading.

Revolvers rarely experience a simple malfunction such as these. If a revolver fails to fire, it is usually ammunition-related and the cure for it is simple: pull the trigger a second time. But if pulling the trigger a second time does not cure the problem, it may be necessary to take the gun to a gunsmith in order to repair it. Revolvers rarely malfunction, but when they do it often requires the help of a trained professional to get them running again.

At the extreme lower end of the price scale, semi-automatic quality degrades considerably. In such cases, revolvers win the reliability test.

Sights: Semi-automatics often (but not always) have the advantage on this one. A lot of revolvers have low-contrast sights which are little more than nearly invisible bumps on the front of the gun. Of course, that problem isn't unique to revolvers, nor are all revolvers like that. But it's definitely necessary to consider the sights when you evaluate a gun for its self-defense potential.

The concern about the safety of the “cocked and locked” (condition 1) pistol is more a matter of perceptions than reality.

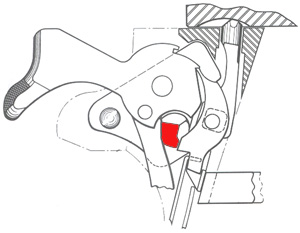

What do we mean by “cocked and locked”? The M1911 pistol is loaded by inserting a charged magazine and racking the slide. This action chambers a cartridge and cocks the hammer of the pistol. The thumb safety is then pushed up toward the sight. This “locks” the pistol. The safety is on and the slide will not move. Inside the gun, a piece of the safety rotates (red area in diagram) and blocks the base of the sear which prevents the sear from releasing the hammer. If the sear hook on the hammer were to break, the sear would be captured by the half-cock notch preventing an accidental discharge. The stud that locks the sear will also not allow the hammer to fall if the safety is engaged.

The 1911 is a single action semi-automatic pistol so it has to be cocked in order to fire. People deal with this in one of three ways: cocked and locked (condition 1), or they chamber a round and carefully lower the hammer (condition 2) so they have to thumb cock the gun to fire it, or they carry it with an empty chamber and rack the slide when they bring it into action (condition 3). I would advise either condition 1 or 3 for home defense, but not condition 2. Condition 2 is not advised under any circumstances. If you are only using the gun for home defense, there is nothing wrong with leaving it in condition 3 with a loaded magazine but with an empty chamber – as long as you have the presence of mind to load the weapon under stress.

When the gun is cocked and locked, the sear is blocked from releasing the hammer! Further, unless a firing grip is on the pistol, thumb safety swept off, and the trigger is pulled, the gun will not go off. This is much safer than a Glock or some of the other new pistol designs which have no external safety. The Glock, by the way, is also pre-cocked which is why it can have a much lighter trigger than a real double action gun. It could be said that the Glock is “cocked and unlocked” which is called “condition zero” with the M1911. Anecdotally, we hear of many more "accidental discharges" with Glocks than with M1911 pattern guns.

The 1911 has two manual safeties. It may look scary, but it is really much safer than many current designs.

If an M1911 has been butchered internally, all bets are off! But if the gun is in good repair, it is safe and will not go off unless the thumb safety is swept off, a firing grip is on the handle, and the trigger is pulled. If you buy a used M1911 pattern pistol, be sure to have it checked out by a competent gunsmith just to insure that the gun has not been modified or made dangerous by a tinkerer and that it is in good working order.

|

You may never have contemplated the situation before, but let's think about it now:

If it is too dark to see what is in your opponent's hands, then you can't identify a threat and you should not shoot, even if you can see your night sights.

If it is light enough to identify your opponent as a threat then is it light enough to see your sights so you don't really need night sights.

Most people are unaware that night sights by themselves are only useful for about 20 minutesduring a normal 24 hour period.

It is in that short window of time, when the sun is going down (or coming up) and there is still enough light to identify your target as a threat, but not enough light to clearly see your sights, that nights sights really shine as an important addition to your weapon.

So should you have night sights on your tactical weapons for the potential need to use them in that very limited tactical niche of 20 minutes in every 24 hour period? YES.

Why?

Because most gun fights occur in low light and night time conditions.

What kind of night sights should you have?

Keep it simple. There are plenty of choices but the three dot (two dots on the rear sight and one dot on the front sight) system is fast and simple.

(reprinted from Front Sight)

The White Light Followed By The Big Bang!

What do you do when it is too dark to identify your opponent as a threat or not?

You use a flashlight to light them up!

Sounds easy, but using a flashlight in the wrong manner can get you killed because as soon as you turn on that light, you are a beacon for incoming rounds.

There are two methods of using a flashlight with your weapon.

The first and easiest method is to attach the flashlight to your weapon. There are a number of companies that offer lights that mount to the forend of your shotgun or rifle and are operated with a pressure pad. When you place pressure on the pad, the light turns on, and as soon as you release the pressure pad, the light turns off. You can also get specialized lights for handguns that mount on the lower frame of the weapon and have a toggle-like switch for immediate on/off control.

The second and more difficult method is to keep your flashlight in your support hand while maintaining the proper stance and grip with your firearm so as you move, your eyes, weapon and light move as one-- ready to deliver an immediate, fight stopping shot when you quickly light up an area and identify a threat-- then turn the light off to move to the next area and out of the way of any incoming return fire from other threats that may have seen the light.

Should you ever need to use your weapon to defend yourself or your loved ones against a violent opponent in a lethal encounter at night, you want your adversary's last visual image to be the white light—immediately followed by the big bang!

I received an intriguing question in my email the other day. In a nutshell, my correspondent wanted to know, "How can the Four Rules apply while the gun is holstered, since many holsters seem to point the weapon in unsafe directions?" Here is my answer:

The Four Rules

1. All guns are always loaded. 2. Never point the gun at anything you are not willing to destroy. 3. Keep your finger off the trigger until your sights are on target (and you have made the decision to shoot). 4. Be sure of your target and what is beyond it.

The second of the Four Rules is the main focal point of this article: "Never point the gun at anything you are not willing to destroy."

This rule applies every time you pick up, hold, or put down a firearm. While you are holding the gun, you never deliberately or cluelessly let it point at stuff you don't want holes in.

But what about muzzle direction when you are not directly holding the gun?

I am of the opinion that a gun, by itself, is an inert object. There is no rational reason to fear a loaded gun lying on the kitchen table as long as no one is touching it. (See footnote1) Gun shop customers do not need to worry about a gun of unknown state (loaded? unloaded?) which is behind a gunshop counter, no matter which direction the gun is pointed, as long as no one is touching it. An untouched firearm is only a thing. It is not a living creature with a mind or a will of its own.

The risk comes when human beings enter the picture. Because human beings are prone to accidents and mistakes, the gun must be pointed in a safe direction whenever human hands touch it. If you cannot pick a firearm up without pointing it in an unsafe direction (or if it is already pointed in an unsafe direction), you should not put your hand on it. If you cannot put a firearm down without pointing it in an unsafe direction, you should not put it down. This is necessary because the mixture of human hand and unsafe direction can cause bad stuff to happen.

With me so far?

When considering whether a holster is "safe" or "not safe," I don't worry much about muzzle orientation while the user's hand is not on the gun. A gun held securely inside a trigger-covering holster, and which is not being handled by a human being, is as safe and as inert as one which is lying on the table untouched.

But notice the italics in the paragraph above. The real danger comes when the gun is being placed into, or withdrawn from, the holster, because that is the point at which human hands get involved in the process. With some holsters, this risk can be avoided entirely. For instance, with a dropped and offset OWB holster on the point of the hip, it takes a near-determined effort of will to cover oneself with the firearm (though I've seen it done!). Yet this sort of rig isn't easily concealed and thus isn't practical for those who want to carry a concealed firearm.

The risk of pointing the gun in an unsafe direction during the process of getting the gun into or out of its holster can be greatly minimized so that it is nearly avoided. This deliberate action takes a very conscious effort of will, and should never become a matter of complacency.

One example of minimizing the risk would be the careful process of safely holstering and unholstering with a shoulder holster. Most smart folks I know who carry with one of these rigs make a conscious effort to place the left elbow high into the air while drawing with the right hand. This moves the brachial artery far away from the risk of inadvertent discharge. (See footnote 2)